My work is driven by a search for social justice, highlighting voices on the political periphery; centring stories from lived experience in bodies that fail the artifice of performing gender, in unruly bodies that defy the construct of disability and unruly minds that fail to conform. This anti-normative position within disability-led theatre proposes an emergent aesthetics – or aesthetics of access.

In excavating my writing, in 18 plays and 2 monologues, it becomes crystal clear that the voices screaming at me throughout, have been women who transgress, women who fail to perform femininity, set out for us in this ablest, patriarchal society. These are women who are branded as ‘wrong’. These are calamitous voices, shaped by, and in opposition to, a dominant Capitalist society obsessed with the white, normatively gendered, symmetrical body promoted in ubiquitous messages across every institution in straight society.

What excites me about the reach of the work I have been absorbed in creating, is the diversity of audiences engaging, who would too often be positioned as the ‘wrong audience’. People who live in long-care hospitals are not ordinarily perceived as artists and storytellers with meaningful contributions to make in our cultural industries. Ticket prices are not the central focus when presenting work in hospital spaces, care homes and secure units. Our audiences break the social rules; defy new-fangled ideas of marketing, outreach and audience segmentation. People need to see themselves reflected in the stories presented onstage and marginalised people, whose lives are often off the radar, don’t fit comfortably in the tidy middle class monuments that we call mainstream theatre.

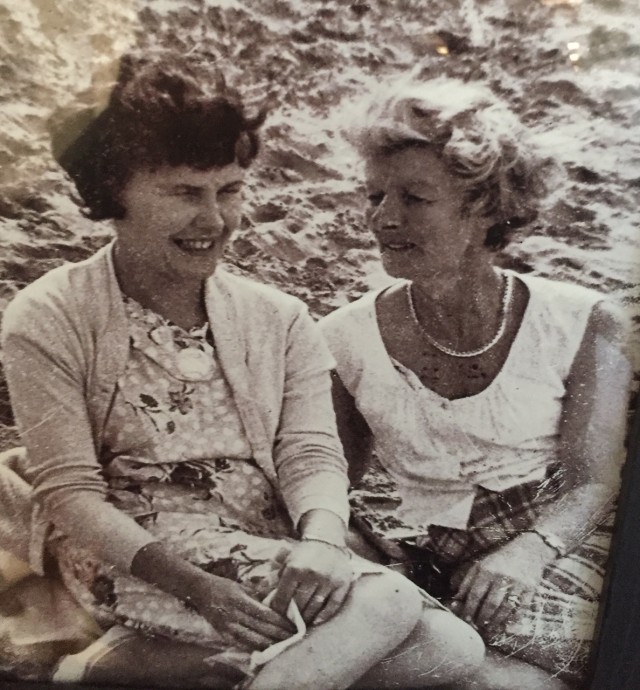

The first time my maternal grandmother, Greta Minto, entered a theatre was at Wilkie House in Cowcross street, Edinburgh Festival, 1980. She came to watch me treading the boards in Lowbrow Theatre’s That Awkward Age and chain-smoked throughout. The ushers gave up after constant reprimands and set a fire bucket beside her with strict instructions re cigarette butts. Greta Minto had a penchant for dancing, a desperate taste in men and nine children. She raised them single handed and was landed with many of her grandchildren, when their Mothers too chose feckless men. Despised by the neighbours’ wives and utterly adored by their husbands, she was the archetypal wrong woman, a canny working class woman with a soft centre. It was from her, and her precious biscuit tin full of yellowing photographs, that I gleaned the stories of our lives. She had sprung me from a council care home at age 3 and a half and saved my battered heart. Come and meet Greta Minto, the original wrong woman who ignited my hunger for storytelling and the impossible search for the truth.

I feel compelled to spend time with all my slapper angels, the wrong women at the heart of my work who stare back from the stage with a gaze that refuses objectification. These are messy girls who make disability sexy, bad girls and wicked women who have refused or been denied the passport conventional beauty gives people. These are women whose embodied experience of the world is to be stared at, measured for medical science and denied access to public spaces. These are the monstrous daughters who were cast aside to ‘let nature takes its course.’

Monstrous Daughters, McNamara J, ch 23, p494-508, Feminism and Museums, Ashton J C, Museums Etc, 2018

They are defiant in their opposition to dodgy attitudes that disable us, hell-bent on shaking up the system, they ‘Piss on Pity’, chain themselves to buses, block the traffic, and refuse to conform.